by Daunt Iago ab Adam, Compaignon du Lorer

(Michael Case, yagowe{AT}gmail.com)

copyright 2001, all rights reserved

History

Around the 1st century AD, Roman writers start to make mention of a fashionable new drink. Apicius, in his lesser known cookbook ‘Cibus Celer'[1], under his recipe for ‘Burgerus et Frius Gallicus’ states that this meal is best served with poculum magnum nectaris colae,’a big cup of dark(?) nectar’. The name of this new drink seems to derive from the Egyptian word ‘kohl’- which was a preparation used to darken the edges of the eyelids- presumably because of its dark colour[2].

For the next millennium this is how things remained; occasional literary references, but no recipes or descriptions. Then, in the 14th century, Sable Nectar guilds started to appear across Europe.[3] The two major centers of production were Coca, in Spain, and Paupisi, in Italy. Because of their fame, cola from these towns became a luxury item, and only the richest people in Europe could serve Paupisi Cola or the Cola of Coca[4]. For a brief period of time the Roman Catholic church tried to get involved in this lucrative business, but R.C. Cola just never caught on, despite threats of eternal damnation. The less affluent members of society were not left out though, as every major town had a Cola makers guild. In England this is evidenced by the popularity of the surnames ‘Cole’, ‘Coleman’, ‘Colegate’ (one who lived near the gate of the Cola guild-hall), and ‘Colebourne’ (one who was born near a vat of Cola)[5].

Another example of Cola’s popularity in England is the following passage from Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur (Penguin Translation) [6]: “And Guinevere came before her lord husband Arthur, and with a kiss gave him a large frothy tankard of Cola. And from the back of the hall Launcelot was heard to say ‘I’ll have what he’s having'”.

Re-Creation

The recipe I used for this reconstruction was found by my Mother in the course of genealogical research. It is from a Norfolk, England Parish Register of the late 19th century, and was in among the Christening, burial, and marriage records:

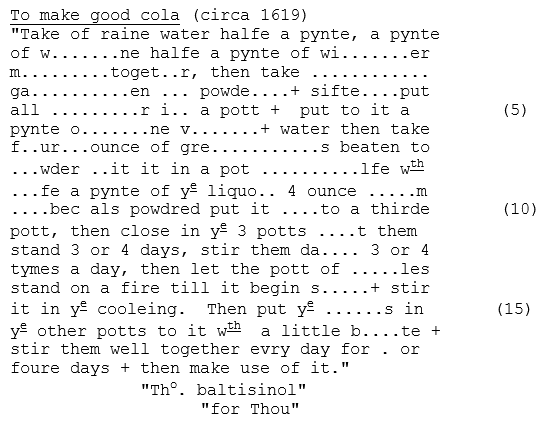

The recipe itself appears to be a copy of an earlier recipe, as it is dated 1619. It is badly ink-stained, but here is what I was able to make out:

I followed the recipe as given, except for the following changes:

- Line 2. I substituted sp……….le for the wi……….er, as wi……….er was to expensive, and sp……….le has a similar texture.

- Line 7. I used ast…………..s instead of gre…………..s, because the gre…………..s is extinct, and the ast…………..s is its closest living relative.

- Line 14. I used the stove instead of a fire, because ever since the ‘Incident’, I’m not allowed to play with fire.

I bottled the finished product in a bottle based on one in the ‘Froissart Chronicles’ miniature of Messire de Craon presenting a bottle of Cola to his cousin, the Duke of Brittany:

The label on the bottle is my attempt at reconstructing the mark of the Cola Guild of Coca, based on descriptions in contemporary writings [7].

[1] Apicius, Marcus Gavius. Cibus Celer; published as “Fast Food of Imperial Rome”, translated by Some Guy with Too Much Time on His Hands. Wayne& Shuster, 1972.

[2] Dictionary, John Q. The Dictionary, Dictionary, Ohio: Dictionary Press, 1985.

[3] Onymous, Anne. “The Rise of the Cola-Guild in 14th C. Europe.” The Journal of Stuff No One Cares About, March, 1956, pp 1066-1298.

[4] Spokesmodel, Famous. “The Paupisi Challenge: A Comparative Study of the Products of the Guilds of Sable Nectar from the Towns of Coca, Spain, and Paupisi, Italy.” Anytown: Bubba’s Printing, 1991.

[5] Alias, A.K.A. The Oxford Dictionary of Phony English Names. Oxford University Press, 1982.

[6] Malory, Thomas. Le Morte d’Arthur; translated by Willy the Wonder Penguin. San Diego: SeaWorld Publishing, 1979.

[7] Ok, I Don’t. Actually Have Any, documentation For This Part; But LikeAnyone: Actually Reads Footnotes, Anyway.